![]()

The Lion of Lanka

______________________

Holding Truth in the palm of his hand, he spread love and knowledge of Siva

______________________

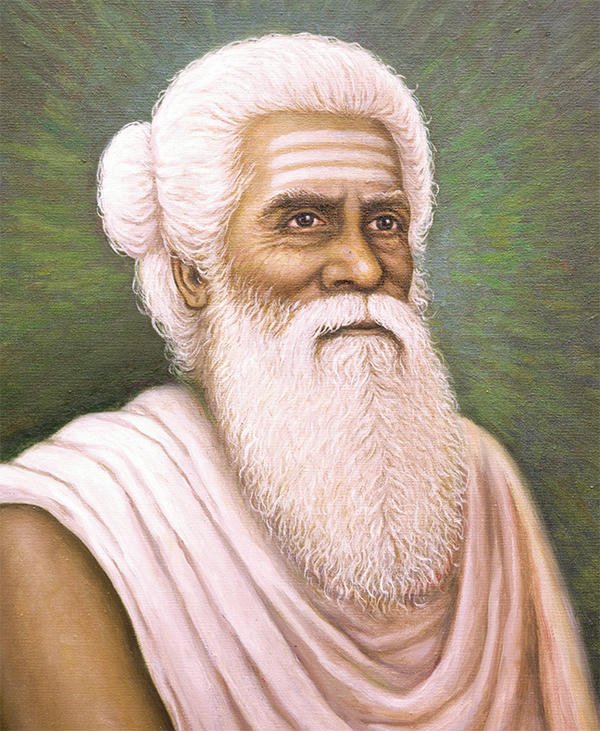

HE STRODE POWERFULLY ALONG THE ROADS AND FIELDS OF HIS ISLAND EACH DAY, and those who saw him coming would move warily to the other side, avoiding the man whose look and voice could pierce the soul and shake the spirit of anyone he met. The white-haired, dark-skinned sage knew their thoughts, and sometimes spoke them aloud. He saw their future, and not infrequently intimated what lay ahead. If you didn’t want to know your inmost Self, you didn’t want to meet Yogaswami on the roadside.

He dressed in white cotton veshti and lived simply, immersed not in things of this world but in an expanded consciousness of the timeless, formless, spaceless Self, Parasiva. Hindus, Christians, Buddhists, Muslims and even atheists sought his wisdom, whether it be delivered with heart-melting love or heart-stopping power. It was 142 years ago that Sage Yogaswami, the satguru of Lanka’s Tamil Hindus for half a century, was born. Inwardly, it is believed, he continues to guide his followers, now scattered around the globe. He is mother, father and guru.

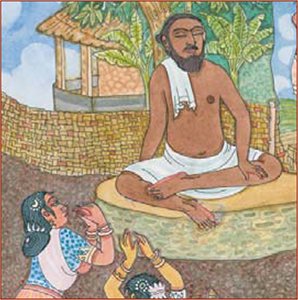

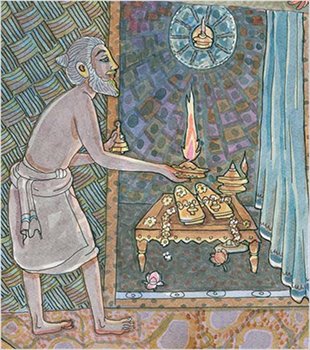

Each morning in his austere hut with its cow-dung floor, Yogaswami would rise before the sun and light camphor to drive the night outside. His daily worship was conducted at a small shrine that held the holy sandals of his satguru, Chellappaswami. He would offer a few flowers to the tiruvadi and light an oil lamp. Soon devotees would arrive, eager to catch him early, before he marched out on the roads, for he would daily walk 20 to 40 miles, alone. He continued this regimen into his eighties. Devotees lucky enough to find him at home morning or evening would quietly come forward, prostrate, touch his feet and wait for his invitation to sit on the woven mats. At his gesture they would sing, usually from the Thevarams, his own Natchintanai songs and other Tamil scriptures and mystic poems.

Tiru T. Sangarappillai Thirunelveli, a Sri Lankan teacher, vividly remembered the ashram during its height in the 1940s and 1950s. “I used to go early in the morning. I would see hand carts, bullock carts and motor cars all lined up on the road. Many would come out bearing fruits, fruit trays and paper bags. Others would enter, taking milk and fruits. On one side people would worship. On the other people would chant the Tamil Vedas. People would wait patiently outside, unable to enter. Inside people would be seated in silence. Such was the sight of the devotees. He would shower his grace on each one. He would sit in perfect silence; then he would sing. He would ask the devotees near him to sing. On many occasions I stayed the night. At times we could sleep only after midnight. Even then, Gurunathan would wake up by four, perform his ablutions and sit in deep meditation. After his meditation, he would worship God with divine songs. In this way his humble ashram slowly became known as a temple to a living God.”

You Are Not these Flesh and Bones

Sage Yogaswami passed his early days in search of God and lived his later life in union with Him [see timeline below]. His devotional and contemplative nature blossomed early on. Even in his childhood he rushed to the temple, cried tears of joy during worship and eagerly undertook penance, such as rolling around the temple in the hot sun. As a young adult he vowed himself to celibacy and renounced a place in his father’s business because it did not allow him time to meditate and study the scriptures he loved so deeply. Around 1890 he found a quiet job as a storekeeper for an irrigation project in Kilinochchi. Here he lived like a yogi, often meditating all night long. He demanded utter simplicity of himself, and purity. Purity would be what he later called on all his devotees to achieve—in mind, speech and action. What appeared to others as incomprehensible austerities were to Yogaswami the natural, necessary and even blissful strivings which brought him ever closer to God, whom he called Siva. Yet, all of this was just a rudimentary preparation for the life he would live with his satguru.

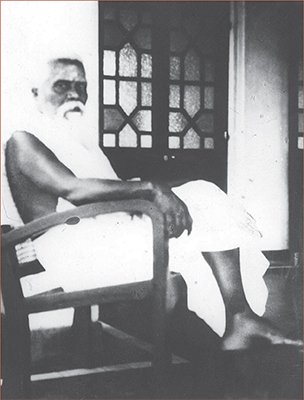

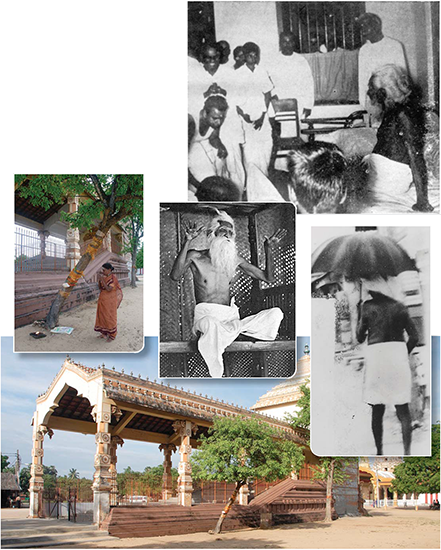

Darshan: On the porch of a devotee’s home on K.K.S. Road, Jaffna, 1950.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Yogaswami’s satguru, Chellappaswami, was intense, unpredictable, unfathomable. Once Yogaswami related to a devotee, “If it were you, you would not have lasted one day with Chellappa.” Yogaswami lived over five years with him, from 1905 to 1911. At another time, a devotee said to Yogaswami, “Chellappaswami has gone away, but he gave everything to you.” Yogaswami at once clarified the process of his guru’s “giving.” “Did I receive it freely?” he retorted. “I obtained it by digging up a mountain!” Chellappaswami’s outward appearance was that of a rumpled vagrant. He would speak to himself and shout at those who passed by. He ate with the crows. Very few people recognized or acknowledged his divine stature. Thus, when Yogaswami began to follow Chellappaswami as a disciple, he was also deemed a madman, a guise not uncommon among masters of the Natha Sampradaya.

Yogaswami knew, however, that the day-to-day life that most people led could not give him the Truth he sought. With his guru he joyfully denied himself the most basic of physical needs, including food, shelter and sleep, and ultimately transcended all of them. After Chellappaswami’s passing in 1911, Yogaswami spent years in intense tapas under an olive (illuppai) tree. The junction at the illuppai tree in the small village of Columbuthurai was well trafficked, so Yogaswami always kept stones at his side to pursuade the curious to move on. His practice during this period was to meditate for three days and nights in the open without moving about or taking shelter from the weather. On the fourth day he would walk long distances, then return to the tree to repeat the cycle.

After some years, Yogaswami allowed a few sincere seekers to approach. They worried that his sadhanas were too severe and urged him to take care of himself. Eventually they persuaded the yogi to move into a nearby one-room thatched hut they had built for him. Even here he forbade devotees to revere or care for him. He prohibited anyone even to rethatch the roof. His closest followers would do so only when he was away, being sure to be finished before his return. Holding fast to his self-reliance, he would not even permit a lamp to be lit by another person. Day and night, over the years, Swami was absorbed in his inner worship, guiding the karmas of thousands, down to every detail of a marriage proposal, a health problem or a close follower’s business transactions. Politicians would always fall at his feet before embarking on their work. Every Sivaratri he would meditate through the entire night. Devotees described seeing brilliant light in place of Swami’s body on these nights. Others were amazed to see him sit statue-like for hours on end. On one occasion which he liked to recall, Swami was seated in perfect stillness, like a stone. A crow flew down and rested several minutes on his head, apparently thinking this was a statue.

A Masterly Life: 1872-1964

At 3:30am on a Wednesday in May of 1872, a son was born to Ambalavanar and Chinnachi Amma not far from the Kandaswamy temple in Maviddapuram, Sri Lanka. He was named Sadasivan. His mother died before he reached age 10, and his aunt and uncle raised him.

In his school days he was bright but independent, often studying alone high in the mango trees. After finishing school, he joined government service as a storekeeper in the irrigation department and served for years in the verdant backwoods of Kilinochchi.

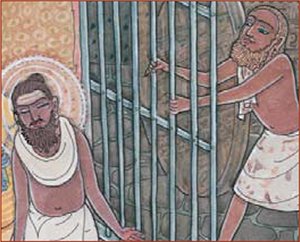

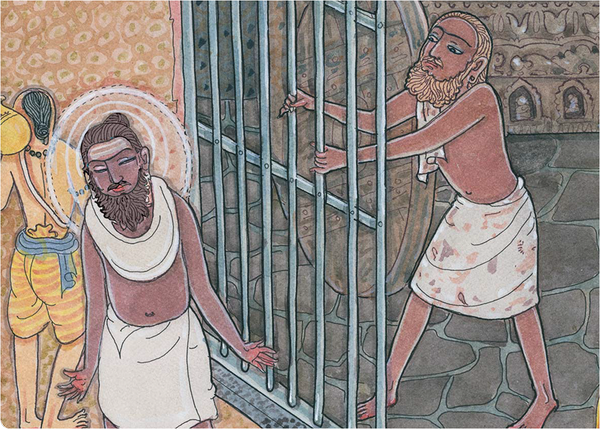

The decisive point of his life came when he encountered his guru outside Nallur Temple. As he walked along the road, Sage Chellappan, a disheveled sadhu, shook the bars from within the chariot shed where he camped and shouted loudly at the passing brahmachari, “Hey! Who are you?” Sadasivan was transfixed by that simple, piercing, inquiry. “There is not one wrong thing!” “It is as it is! Who knows?” the jnani roared, and suddenly everything vanished in a sea of light. At a later encounter amid a festival crowd, Chellappaswami ordered him, “Go within; meditate; stay here until I return.” He came back three days later to find Yogawami still waiting for his master.

Yogaswami surrendered himself completely to his guru, walking often to Nallur Temple to be with the master. Life for him became one of intense spiritual discipline, severe austerity and stern trials.

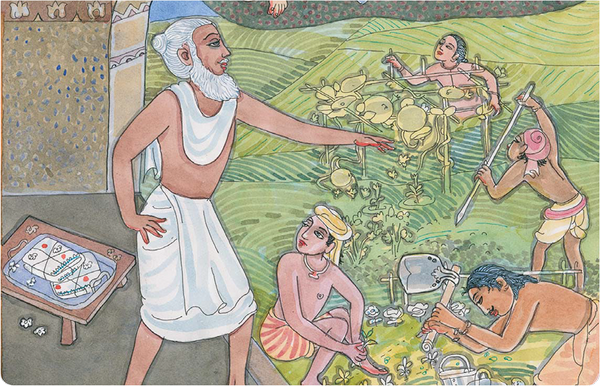

ART BY S . RAJAM

One such trial was a continuous meditation which Chellappaswami demanded of Sadasivan and fellow aspirant Katiravelu in 1910. For 40 days and nights the two disciples sat upon a large flat rock. Chellappaswami came each day and gave them only tea or water. On the morning of the fortieth day, the guru cooked a meal—but instead of feeding the hungry yogis, he threw the food high in the air, proclaiming, “That’s all I have for you. Two elephants cannot be tied to one post.” It was his way of saying two powerful men cannot reign in one place. Following this ordination, he sent the initiates in different directions.

Katiraveluswami was not seen again, and it was thought he went to South India. Yogaswami began the life of the wandering ascetic, begging for his food, visiting temples and chanting hymns. He undertook an arduous foot pilgrimage to Kathirgama Temple in the far South. In 1911, after he returned to Jaffna, two devotees witnessed Yogaswami’s “coronation.” He met with Chellappaswami, who greeted him, saying, “Come! I give the crown of Kingship to you!—for as long as the universe endures.”

Chellappaswami passed on in 1911. Yogaswami, obeying his guru’s last orders, sat on the roots of a huge olive tree at Columbuthurai. Under this tree he stayed, exposed to the roughest weather, unmindful of the hardship and serene as ever. This was his home for the next few years. Intent on his meditative regimen, he would chase away curious onlookers and worshipful devotees with stones and harsh words. After much persuasion, he was convinced to move into a nearby thatched hut provided by a devotee.

Few recognized his attainment. But this changed significantly one day when he traveled by train from Colombo to Jaffna. An esteemed and scholarly pandit riding in another car repeatedly stated he sensed a “great jyoti” (a light) on the train. When he saw Siva Yogaswami disembark, he cried out, “You see! There he is.” The pandit canceled his discourses, located and rushed to Siva Yogaswami’s ashram and prostrated at his feet. His visit to the hut became the clarion call that here indeed was a worshipful being.

From then on people of all ages and all walks of life, irrespective of creed, caste or race, went to Yogaswami. They sought solace and spiritual guidance, and none went away empty-handed. He influenced their lives profoundly. Many realized how blessed they had been only after years had passed.

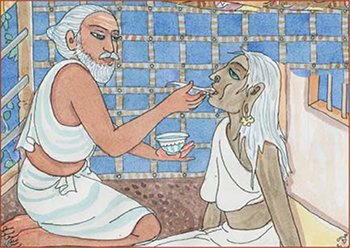

Yogaswami’s infinite compassion never ceased to impress. He would regularly walk long miles to visit Chellachchi Ammaiyar, a saintly woman immersed in meditation and tapas. Yogaswami would feed her and attend to duties as she sat in samadhi. Upon her directive, her devotees, some the most learned elite of Sri Lanka, transferred their devotion to Satguru Yogaswami after her passing.

He would mysteriously enter the homes of devotees just when they needed him, when ill or at the time of their death. He would stand over them, apply holy ash and safeguard their passage. He was also known to have remarkable healing powers and a comprehensive knowledge of medicinal uses of herbs. Countless stories tell how he healed from afar. He would prepare remedies for ill devotees. Cures always came as he prescribed.

When not out visiting devotees, Yogaswami would receive them in his hut. From dawn to dusk they came and listened, rapt in devotion. In 1940 Yogaswami went to India on pilgrimage to Varanasi and Chidambaram. His famous letter from Varanasi states, “After wandering far in an earnest quest, I came to Kashi and saw the Lord of the Universe—within myself. The herb that you seek is under your feet.”

One day he visited Sri Ramana Maharshi at his ashram at Arunachala Hill. The two simply sat all afternoon, facing each other in eloquent silence. Not a word was spoken. Back in Jaffna he explained, “We said all that had to be said.”

Followers became more numerous, so he gave them all work to do, seva to God and to the community. In December of 1934 he had them begin his monthly journal, Sivathondan, meaning both “servant of Siva” and “service to Siva.”

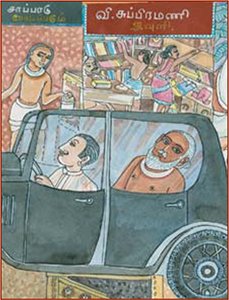

As the years progressed, Swami more and more enjoyed traversing the Jaffna peninsula by car, and it became a common sight to see him chaperoned through the villages.

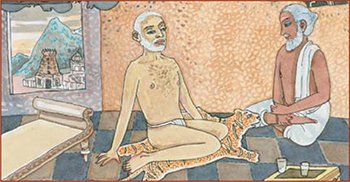

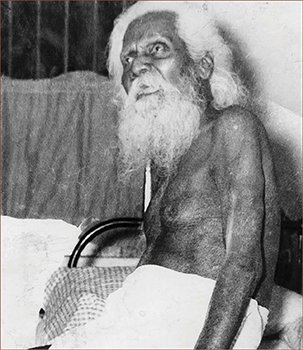

On February 21, 1961, Swami went outside to give his cow, Valli, his banana leaf after eating, as he always did. Valli was a gentle cow, but this day she threw her head powerfully, struck his leg and knocked him down. The hip was broken, not a trivial matter for an 88-year-old in those days. Swami spent months in the hospital, and once released was confined to a wheelchair.

Devotees were heart-stricken by the accident, yet their guru remained unshaken. He ever affirmed, “Siva’s will prevails within and without—abide in His will.”

Swami was now confined to his ashram, and devotees came in even greater numbers, for he could no longer escape on long walks. He was, he quipped, “captured.” With infinite patience and love, he meted out his wisdom, guidance and grace in his final years.

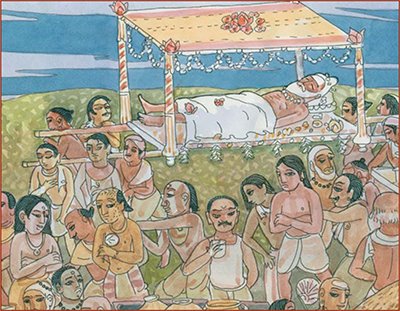

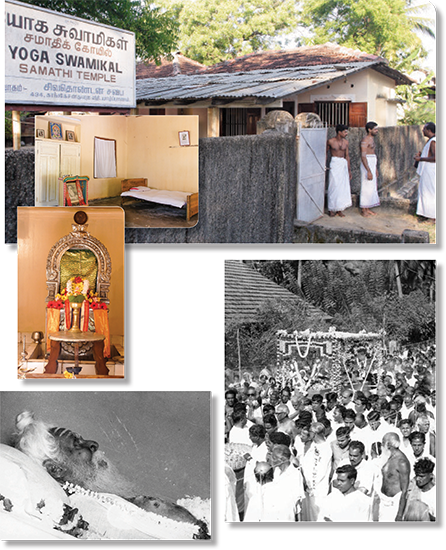

At 3:18 am on a Monday in March of 1964, Yogaswami passed quietly from this Earth at age 91. The nation stopped when the radio spread news of his Great Departure, and devotees thronged from every corner of the island to bid him farewell. Tens of thousands carried and accompanied his bier to the cremation grounds the following day. Though enlightened souls are often interred, it was his wish to be cremated. Stories of his life are told and retold. His hut in Columbuthurai, from which he ruled Lanka for 50 years, is a sacred site in Jaffna, and a small temple complex was erected there. This year, 2014, was celebrated as the 50th anniversary of his Mahasamadhi. Yogaswami’s teachings and the Nandinatha lineage live on through the work of Kauai’s Hindu Monastery in Hawaii, USA.

Soften Your Heart And Let It Melt

As the years passed, Swami relented a little, permitting his ever-increasing fold to express their natural devotion. He allowed his hut to be cleaned, the snakes removed and a new cow-dung floor installed.

Yogaswami was equally feared and loved. Even his ardent devotees approached him with trepidation, for he somehow knew their innermost thoughts and feelings—the good and otherwise. If their motivation was not pure, he would berate them or pelt them with stones or see they never entered his gate again. He was not a stranger to rough language, using it to keep the wrong people at bay. When one of his disciples complained about his sometimes incendiary temper, he replied, “Is not a big fire necessary to burn so much rubbish?”

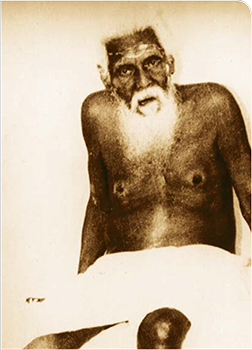

In meditation: One day Yogaswami was visiting a devotee’s home, meditating in the early hours of the day. The family’s 19-year-old son, Samy Pasupatti, took the photo secretly, but later confessed his unauthorized intrusion. Yogaswami, who had denied all requests for a photo previously, laughed, and told the boy it was done and he could keep it. It became the most famous pose for the great satguru.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Still, even those he rebuked felt blessed, reckoning it a spiritual cleansing. Susunaga Weeraperuma, a Sinhalese Buddhist, recounted that in his Dr. S. Ramanathan Chunnakam recalled a humbling lesson received in 1920. “I went to visit Swami with advocate Somasunderam of Nallur. In my youth I was proficient in sword fighting and similar arts. As a result, I was a little arrogant. While on the way to the ashram, Swami appeared in the middle of the road and felled me. I can never forget this incident. Even martial arts instructors cannot show the proficiency in their hands and legs that Swami displayed. After I got up, Swami took me into his hut and showered me with love. But it was only years later that I understood the divine sport that made me eat the dust on the road to Swami’s ashram.”

Contemplative Contemporaries

Yogaswami revered and was deeply motivated by other Hindu leaders of his time. In 1889, Swami Vivekananda was received in Jaffna by a large crowd and taken in festive procession along Columbuthurai Road. As he neared the illuppai tree where Yogaswami later performed his tapas, Vivekananda stopped the procession and disembarked from his carriage. He explained that this was sacred ground and he preferred to walk past rather than ride. He described the area around the tree as an “oasis in the desert.” The next day, the 18-year-old Yogaswami attended Vivekananda’s public speech. He later recalled that Vivekananda paced powerfully across the stage and “roared like a lion”—making a deep impression on the young yogi. Vivekananda began his address with “The time is short but the subject is vast.” This statement went deep into Yogaswami’s psyche. He repeated it like a mantra to himself and spoke it to devotees throughout his life.

“Don’t go halfway to meet difficulties. Face them as they come to you; God is always with you, and that is the greatest news I have for you.”

YOGASWAMI

On one occasion, Yogaswami divulged his respect for Mahatma Gandhi. He related, “Two European ladies came to see me. They had been in India to see Mahatma Gandhi and wanted a message from me. I asked them what Gandhi had told them. The Mahatma had said, ‘One God, one world.’ I told them I could not think of a better message and sent them away.” Yogaswami also met the great sage Ramana Maharshi on a pilgrimage to India.

Good Thoughts

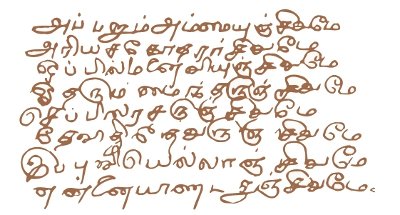

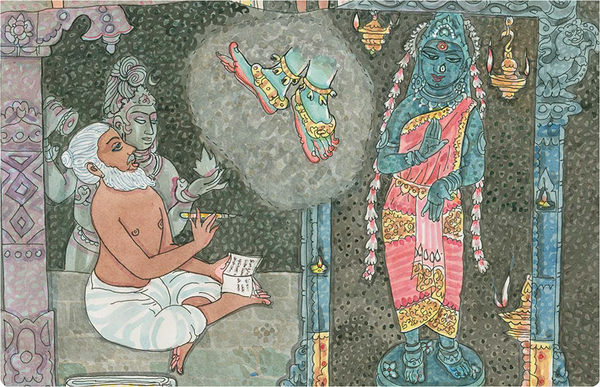

Yogaswami articulated his own teachings in over 3,000 poems and songs called Natchintanai, meaning “good thoughts,” urging seekers to follow dharma, serve selflessly and realize God within. These gems flowed spontaneously from him, sometimes in a devotee’s home, often while seated at the small side shrine to Parvati in a nearby Siva temple he frequented. Any devotee present would write them down, and he occasionally scribed them himself [see p. 72]. His Natchintanai have been published in several books and through the primary outlet and archive of his teachings, the Sivathondan, a monthly journal he established in 1934.

These publications preserve the rich legacy of Swami’s sayings and sweet songs. The Natchintanai are enchantingly composed and a joy to sing. Swami’s devotees soulfully intone them during their daily worship and discipline, as much today as when the great sage walked the narrow lanes of Jaffna. Natchintanai are a profound and powerful tool for teaching and preserving Hinduism’s core truths.

Based in pure Saiva Siddhanta, the Natchintanai affirm the oneness of man and God. Though Yogaswami dauntlessly stressed the nondual nature of Reality, he could never be labeled an Advaitic or Vedantin. He acknowledged the utmost peaks of consciousness but also the foothills that must be traversed to reach that summit, and constantly spoke of the Nayanars, the 63 Tamil saints who embodied his Siddhanta heritage and ideals. His message was summarized by him in two words, Sivadhyana and Sivathondu—meditation on Siva and service to Siva. With these two, he ever asserted, one can complete the journey.

Twilight years: This rare photo of Yogaswami was taken inside his hut after a return from the hospital. Days earlier, the 88-year-old had broken his hip when his cow, Valli, threw her head and tossed him to the ground. Devotees, not shown, have come to touch his feet.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

The Power of Parampara

Glimpses of the Life and Teachings of Yogaswami

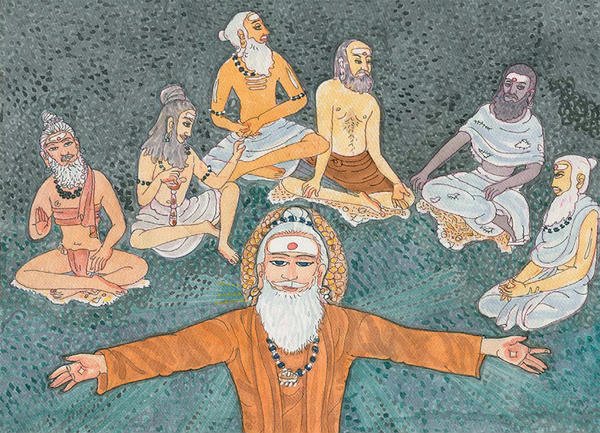

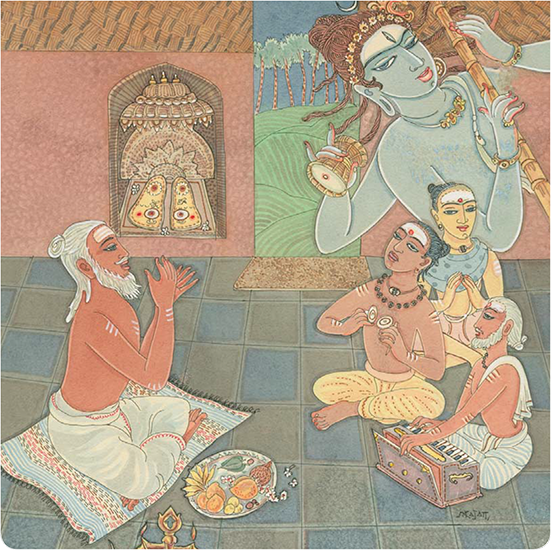

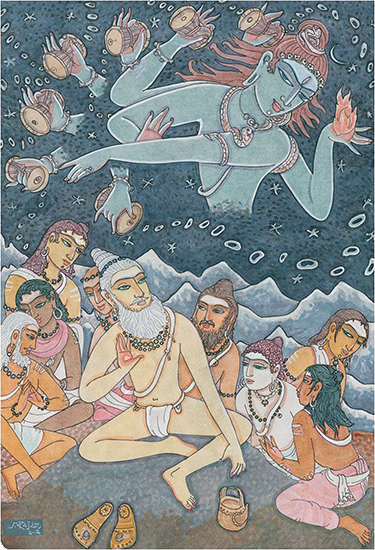

OGASWAMI WAS A MYSTERIOUS MEDLEY: A solitary mystic who drew crowds to his feet, a loving guru who often spoke harshly, a man with little education who wrote literately of the highest philosophy, a yogi who loved to drive through the villages, a simple man who confounded everyone who met him. His life is recounted in the 2009 Himalayan Academy book The Guru Chronicles, an 816-page spiritual biography of the Nandinatha Sampradaya’s Kailasa Parampara, of which Yogaswami was the 20th century’s most highly regarded satguru. The book includes the stories of his life, his training with Chellappaswami, his philosophical insights and his relationship with tens of thousands of devotees and seekers. S. Rajam of Tamil Nadu, India, was commissioned to bring these true stories to life in art. The renowned artist worked for two years, bringing forth a masterly depiction of the Jaffna culture and the personalities that surrounded Yogaswami, all shared in these pages. The art above shows Yogaswami on the far right, with the primary satgurus in his lineage to his right: Chellappaswami, Kadaitswami, Rishi from the Himalayas, Tirumular and Nandinatha. His successor, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, is below, arms outstretched.

OGASWAMI WAS A MYSTERIOUS MEDLEY: A solitary mystic who drew crowds to his feet, a loving guru who often spoke harshly, a man with little education who wrote literately of the highest philosophy, a yogi who loved to drive through the villages, a simple man who confounded everyone who met him. His life is recounted in the 2009 Himalayan Academy book The Guru Chronicles, an 816-page spiritual biography of the Nandinatha Sampradaya’s Kailasa Parampara, of which Yogaswami was the 20th century’s most highly regarded satguru. The book includes the stories of his life, his training with Chellappaswami, his philosophical insights and his relationship with tens of thousands of devotees and seekers. S. Rajam of Tamil Nadu, India, was commissioned to bring these true stories to life in art. The renowned artist worked for two years, bringing forth a masterly depiction of the Jaffna culture and the personalities that surrounded Yogaswami, all shared in these pages. The art above shows Yogaswami on the far right, with the primary satgurus in his lineage to his right: Chellappaswami, Kadaitswami, Rishi from the Himalayas, Tirumular and Nandinatha. His successor, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, is below, arms outstretched.

Without a satguru, all philosophy, knowledge and mantras are fruitless. Him alone the Gods praise who is the satguru, keeping active what is handed down to him by tradition. Therefore, one should seek with all effort to obtain a preceptor of the unbroken tradition, born of Supreme Siva.

Kularnava Tantra 10.1

Meeting the Master: Tens of thousands found

their way to Yogaswami’s humble hut, there

to sing in the presence of a rare being and

be graced by his illumined words.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

I see God everywhere. I worship everywhere. All are God! I can say that because I don’t know. He who does not know, knows all. If you don’t know, you are pure. Not knowing is purity. Not knowing is knowing. Then you are humble. If you know, then you are not pure. People will say they know and tell you this and that. They don’t know. Nobody knows. You don’t want to know. I don’t know. Why do you want to know? Just be as you are. You don’t want to know. Let God act through you. Give up this “I want to know.” Let God speak. This idea of knowing must be surrendered. Think, think, think. Then you will come to “I do not know.” I don’t know. You don’t know. Nobody knows. It is so. Who knows? If I can say, “I know nothing,” then I am God.

Yogaswami

Yogaswami after his accident, age 88.

The Day I Met Yogaswami

By Sam Wickramasinghe, Colombo, Sri Lanka

OMETIME IN THE MID 1950S, SAM WICKRAMASINGHE, a sinhalese Buddhist, visited Yogaswami with a Tamil friend from Jaffna. Sam was a sincere seeker who had heard much about Yogaswami but had never visited him. Sam had met his new friend one day while walking along the seashore in Colombo. Soon after they exchanged greetings, the elder began telling him about Yogaswami with great enthusiasm, then scolded him for never having visited Swami: “It is disgraceful that you haven’t bothered to visit our sage who lives on this island.” The man offered to pay Sam’s train fare to Jaffna and invited him to live in his home in Tellippallai as long as he wished. Using the pen name Susunaga Weeraperuma, Sam recounted his experience in a small book he wrote in 1970, called Homage to Yogaswami.

OMETIME IN THE MID 1950S, SAM WICKRAMASINGHE, a sinhalese Buddhist, visited Yogaswami with a Tamil friend from Jaffna. Sam was a sincere seeker who had heard much about Yogaswami but had never visited him. Sam had met his new friend one day while walking along the seashore in Colombo. Soon after they exchanged greetings, the elder began telling him about Yogaswami with great enthusiasm, then scolded him for never having visited Swami: “It is disgraceful that you haven’t bothered to visit our sage who lives on this island.” The man offered to pay Sam’s train fare to Jaffna and invited him to live in his home in Tellippallai as long as he wished. Using the pen name Susunaga Weeraperuma, Sam recounted his experience in a small book he wrote in 1970, called Homage to Yogaswami.

It was a cool and peaceful morning, except for the rattling noises owing to the gentle breeze that swayed the tall and graceful palmyra trees. We walked silently through the narrow and dusty roads. The city was still asleep. We approached Swami’s tiny thatched-roof hut that had been constructed for him in the garden of a home outside Jaffna. Yogaswami appeared exactly as I had imagined him to be. At 83 he looked very old and frail. He was of medium height, and his long grey hair fell over his shoulders. When we first saw him, he was sweeping the garden with a long broom. He slowly walked towards us and opened the gates.

“I am doing a coolie’s job,” he said. “Why have you come to see a coolie?” He chuckled with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. I noticed that he spoke good English with an impeccable accent. As there is usually an esoteric meaning to all his statements, I interpreted his words to mean this: “I am a spiritual cleanser of human beings. Why do you want to be cleansed?”

He gently beckoned us into his hut. Yogaswami sat cross-legged on a slightly elevated neem-wood platform, which also served as his austere bed, and we sat on the floor facing him. We had not yet spoken a single word. That morning we hardly spoke; he did all the talking. Swami closed his eyes and remained motionless for nearly half an hour. He seemed to live in another dimension of his being during that time. One wondered whether the serenity of his facial expression was attributable to the joy of his inner meditation. Was he sleeping or resting? Was he trying to probe into our minds? My friend indicated with a nervous smile that we were really lucky to have been received by him. Yogaswami suddenly opened his eyes. Those luminous eyes brightened the darkness of the entire hut. His eyes were as mellow as they were luminous—the mellowness of compassion.

I was beginning to feel hungry and tired, and thereupon Yogaswami asked, “What will you have for breakfast?” At that moment I would have accepted anything that was offered, but I thought of idli [steamed rice cakes] and bananas, which were popular food items in Jaffna. In a flash there appeared a stranger in the hut who respectfully bowed and offered us these items of food from a tray. A little later my friend wished for coffee, and before he could express his request the same man reappeared on the scene and served us coffee.

After breakfast Yogaswami asked us not to throw away the banana skins, as they were for the cow. He called loudly to her and she clumsily walked right into the hut. He fed her the banana skins. She licked his hand gratefully and tried to sit on the floor. Holding out to her the last banana skin, Swami ordered, “Now leave us alone. Don’t disturb us, Valli. I’m having some visitors.” The cow nodded her head in obeisance and faithfully carried out his instructions.

Yogaswami closed his eyes again, seeming once more to be lost in a world of his own. I was indeed curious to know what exactly he did on these occasions. I wondered whether he was meditating. There came an apropos moment to broach the subject, but before I could ask any questions he suddenly started speaking.

“Look at those trees. The trees are meditating. Meditation is silence. If you realize that you really know nothing, then you would be truly meditating. Such truthfulness is the right soil for silence. Silence is meditation.” He bent forward eagerly. “You must be simple. You must be utterly naked in your consciousness. When you have reduced yourself to nothing—when your self has disappeared, when you have become nothing—then you are yourself God. The man who is nothing knows God, for God is nothing. Nothing is everything. Because I am nothing, you see, because I am a beggar, I own everything. So nothing means everything. Understand?”

“Tell us about this state of nothingness,” requested my friend with eager anticipation.

“It means that you genuinely desire nothing. It means that you can honestly say that you know nothing. It also means that you are not interested in doing anything about this state of nothingness.” What, I speculated, did he mean by “know nothing?” The state of “pure being” in contrast to “becoming?” He responded to my thought, “You think you know, but, in fact, you are ignorant. When you see that you know nothing about yourself, then you are yourself God.

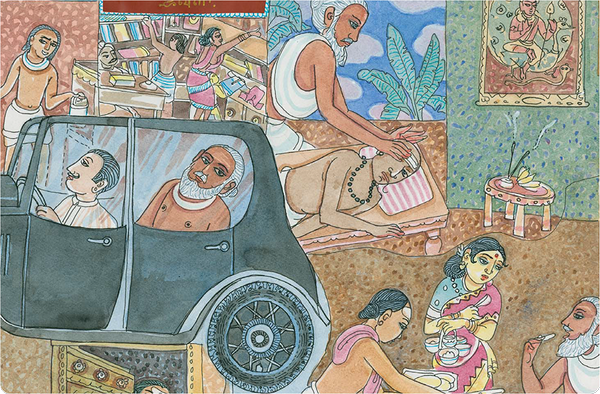

Lives transformed: Yogaswami shown moving about in the community.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Though the state desired was thoughtless and wordless, he taught through a few favorite aphorisms in pithy expressions, to be plumbed later in silence. Three of these aphorisms I shall report here: “Just be!” or “Summa iru” when he said it in Tamil. “There is not even one thing wrong.” “It is all perfect from the beginning.” He applied these statements to the individual and to the cosmos. Order was a truth deeper than disorder. We don’t have to develop or do anything, because, essentially, in our being, we are perfectly in order here and now—when we are here and now.

DR. JAMES GEORGE

Dr. James George of Canada, now age 96, a lifetime scholar and diplomat and former High Commissioner to Ceylon, India and Iran

“Who Am I?”

By Dr. James George, Toronto, Canada

R. JAMES GEORGE WAS PROFOUNDLY INFLUENCED BY SWAMI. The following is an account of his visits to the sage’s hut in Columbuthurai.

R. JAMES GEORGE WAS PROFOUNDLY INFLUENCED BY SWAMI. The following is an account of his visits to the sage’s hut in Columbuthurai.

The Tamils of Sri Lanka called him the Sage of Jaffna. His thousands of devotees, including many Sinhalese Buddhists and Christians, called him a saint. Some of those closest to him referred to him as the Old Lion, or Bodhidharma reborn, for he could be very fierce and unpredictable, chasing away unwelcome supplicants with a stick. I just called him Swami. He was my introduction to Hinduism in its pure Vedanta form, and my teacher for the nearly four years I served as the Canadian High Commissioner in what was still called Ceylon in the early sixties when I was there.

For the previous ten years I had been apprenticed in the Gurdjieff Work, and it was through a former student of P. D. Ouspensky, James Ramsbotham (Lord Soulbury), and his brother Peter, that, one hot afternoon, not long after our arrival in Ceylon, I found myself outside a modest thatched hut in Jaffna, on the northern shore of Ceylon, to keep my first appointment with Yogaswami.

I knocked quietly on the door, and a voice from within roared, “Is that the Canadian High Commissioner?” I opened the door to find him seated cross-legged on the floor—an erect, commanding presence clad in a white robe, with a generous topping of white hair and long white beard. “Well, Swami,” I began, “that is just what I do, not what I am.” “Then come and sit with me,” he laughed uproariously.

I felt bonded with him from that moment. He helped me to go deeper towards the discovery of who I am, and to identify less with the role I played. Indeed, like his great Tamil contemporary, Ramana Maharshi of Arunachalam, in South India, Yogaswami used “Who am I?” as a mantra as well as an existential question. He often chided me for running around the country, attending one official function after another, and neglecting the practice of sitting in meditation. When I got back to Ceylon from home leave in Canada, after visiting, on the way around the planet, France, Canada, Japan, Indonesia and Cambodia, he sat me down firmly beside him and told me that I was spending my life-energy uselessly, looking always outward for what could only be found within.

“You are all the time running about, doing something, instead of sitting still and just being. Why don’t you sit at home and confront yourself as you are, asking yourself, not me, ‘Who am I? Who am I? Who am I? Who am I? Who am I? Who am I?’” His voice rose in pitch, volume and intensity with each repetition of the question until he was screaming at me with all his force.

Then suddenly he was silent, very powerfully silent, filling the room with his unspoken teaching that went far beyond words, banishing my turning thoughts with his simple presence. In that moment I knew without any question that I AM; and that that is enough; no “who” needed. I just am. It is a lesson I keep having to relearn, re-experience, for the “doing” and the “thinking” takes me over again and again as soon as I forget.

Another time my wife and I brought our three children to see Yogaswami. Turning to the children, he asked each of them, “How old are you?” Our daughter said, “Nine,” and the boys, “Eleven” and “Thirteen.” To each in turn Yogaswami replied solemnly, “I am the same age as you.” When the children protested that he couldn’t be three different ages at once, and that he must be much older than their grandfather, Yogaswami just laughed, and winked at us, to see if we understood.

At the time we took it as his joke with the children, but slowly we came to see that he meant something profound, which it was for us to decipher. Now I think this was his way of saying indirectly that although the body may be of very different ages on its way from birth to death, something just as real as the body, and for which the body is only a vehicle, always was and always will be. In that sense, we are in essence all “the same age.”

After I had met Yogaswami many times, I learned to prepare my questions carefully. One day, when I had done so, I approached his hut, took off my shoes, went in and sat down on a straw mat on the earth floor, while he watched me with the attention that never seemed to fail him. “Swami,” I began, “I think...” “Already wrong!” he thundered. And my mind again went into the nonconceptual state that he was such a master at invoking, clearing the way for being.

Looking at the world as it is now, thirty years after his death, I wonder if he would utter the same aphorisms with the same conviction today. I expect he would, challenging us to go still deeper to understand what he meant. Reality cannot be imperfect or wrong; only we can be both wrong and imperfect, when we are not real, when we are not now!

Bringing everyone to Siva: Yogaswami ruled the community and was visited daily by devotees seeking his blessings. He answered their queries, sang sacred songs with them, and spoke of Siva as the All in all. Thousands of stories unfolded inside that hut as he drew them all into Sivadhyanam and Sivathondu, meditation on Siva and service to Siva.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

From 1911 to 1915 Chellappaswami did not allow Yogaswami to be with him. On one occasion Yogaswami visited Chellappaswami’s hut. Suddenly the sage emerged, shouting and swearing at him to get out of there. Realizing that his guru was about to start throwing things, Yogaswami turned on his heels and retreated the way he came. “Stand on your own two feet!” the sage bellowed after him.

Chellappaswami would come to the illupai tree occasionally, observe his disciple and go. Once when his guru came, Yogaswami stood up and went to worship him. Chellappaswami glared, scolding, “What! Are you seeing duality? Try to see unity.” Chastened by these words, Swami remained rooted to the spot.

He Touched the Soul in All

NE MORNING AN OLD MAN CAME TO VISIT YOGASWAMI who was Swami’s same age and had known him for a long time. He was living in an old folks’ home run by the government and subsisting on a small pension. Entering the hermitage, he placed a bunch of bananas at Swami’s feet and prostrated. Swami was clearly happy to see him. This companion had come often, and Swami enjoyed his company.

NE MORNING AN OLD MAN CAME TO VISIT YOGASWAMI who was Swami’s same age and had known him for a long time. He was living in an old folks’ home run by the government and subsisting on a small pension. Entering the hermitage, he placed a bunch of bananas at Swami’s feet and prostrated. Swami was clearly happy to see him. This companion had come often, and Swami enjoyed his company.

“Good morning, old friend,” Swami greeted him. Then they talked for some time about the man’s situation. How had he been? Had he been enjoying good food? Finally, Swami asked him by what means he had traveled. “On the train, Swami,” came the answer.

“But trains are crowded these days and difficult for an old man like you to climb on and off of. It’s a great deal of trouble for you to travel on the train,” Swami replied. “Oh, Swami, I only think of one thing when I set out to see you, and that carries me along. No difficulties at all coming here.”

“I know what you mean,” Swami replied, “but traveling is really too much trouble for you, and costly, too, these days. You needn’t come, you know. There are other ways of visiting me.” Swami fell quiet but his friend continued, “Oh, Swami, coming to visit you every few months gives my life a wonderful peace. It is worth any amount of trouble.”

Swami kept his silence, allowing that conversation to die away completely, then spoke again. “Tell me, old friend, you have lived a long time now, and have lived a good life; do you feel at peace? What stands out in your mind as the most important thing in your life?”

“You know, Swami, I have given that question a lot of thought these days. Everything that I used to think was important is gone. My family is gone. My friends are gone. My home is gone and my work is finished. My body is old and feeble. Yet I go on the same. I always find love in my heart. I think that probably love is the most important thing in life.” Swami was moved and pleased by the answer. “You and I are the same,” he said. “That’s what I find important, too.”

After the man left, Swami told those who were gathered around that to have a simple heart, as this man did, is worth more than anything else. “Everything is so simple, but man with his monkey mind and his idea of ‘I’ and ‘mine’ makes a complex mess of it, then blames everyone around him because he cannot see the truth. This man will leave his body in a few days. It will be simple and natural for him. And he has something that he will carry on into his future lives: a fine and simple sense of life. Everything will be easy for him.” The man died a few days later.

Know Thy Self by Thyself

Yogaswami would say, “If you are a king, will you have contentment? If you are a beggar, will you have contentment? Whatever your walk in life may be, you will only have contentment through knowing yourself by yourself.” It was a persistent call to action, a prescription he wrote up frequently, urging devotees to undertake sadhana, to curb the mind, to discipline their life and live in Siva’s perfect grace.

Anyone who came to Swami with an honest and simple heart was well received. When children visited, he would lift them onto his lap and tell those around him, “This child and I are the same age. We speak the same language. And we understand things the rest of you have forgotten.”

Sometimes he would ask children to sing for him. They would sing the Natchintanai hymns he had composed, and he would join in, perhaps singing in a child’s airy voice. As often as not, he would ask the child if he or she wanted anything, a toy, or something else. If a wish was expressed, he would send out for it immediately.

He was also stern with children. He told them that the most important thing to learn was obedience. Once he wrote a letter to a boy, advising: “Be obedient. Listen to the advice of your father, mother, elder sisters, younger brother, as well as your uncle, aunt and elder brothers. Always set an example in obedience. Siva does all.” “Oh, it might seem hard,” he would say, “But it is the best way of living in the world. Even I take orders. My orders come from within. Later you, too, will receive orders from within.”

Most people came like children and were obedient to his orders. He was so close to his devotees that they would rush to tell him when a child was born, sometimes before they told the rest of their family. They would have a special offering ready to take to Swami so that when the child was born they wouldn’t have to stop at a shop, but could go straightaway to see him and receive his blessing for the child.

Often he would greet these new fathers at his compound gate and shout at them with a twinkle in his eye, “Great news I have for you. A lovely girl named Thiripurasundari was born this morning. Come, let us celebrate.” That, of course, was exactly the news the father was bringing, except that he hadn’t yet named his daughter! Many people in Jaffna received their names from Swami in such ways.

Markandu, the Surveyor

Markanduswami, a close devotee of Yogaswami from the time they met in 1931, was a lifelong bachelor who wanted to renounce the world and take sannyasa in the middle of his career. Yogaswami told him to continue in his profession as a surveyor. Finally, when Markanduswami’s retirement came at age 6o, Yogaswami surprised him by arranging for a kutir to be built in a small coconut grove in the village of Kaithadi, a hut with one room, an open porch and a concrete floor, with walls and roof of woven palm fronds. He settled his disciple there and looked after him for years.

His foremost sadhana, a difficult one they say, was to speak only the words of his guru, so everyone who spent an hour with him would hear, again and again, “Yogaswami said....” “Yogaswami taught us....” He was amazingly faithful to this discipline of not giving out his own wisdom, though he was deeply endowed. Standing on his porch or perched on a raised neem seat with four posts and a canopy, he would explain excitedly that Yogaswami gave him the following sadhana, his indirect way of inviting seekers to control their own minds: “Sit in one place. Do not move. Watch where your mind goes; watch the fellow. First, he’ll be in Kandy, then go to Colombo, then to Jaffna, all in a fraction of a second. Keep track of every place he goes. If he goes one hundred places and you have caught only ninety-nine, you fail. As you progress in this sadhana, you will begin to pick up things coming from within. When you get messages from inside, you must deliver them to those who need to know. It will be a great help to them.”

On one Mahasivaratri evening Yogaswami paid a surprise visit to Markanduswami’s hut and told the old sadhu, “We shall observe this Mahasivaratri vrata with meditation only.” That night, for them, there were no pujas, no chanting of Natchintanai, Agamas or Puranas, only meditation in absolute silence. T. Sivayogapathy shared:

“Markanduswami was a man of few words and avoided involving himself in the public life. He knew the whole corpus of Natchintanai songs by heart and always quoted Natchintanai when talking about Hinduism and spiritualism. Yogaswami is said to have told devotees, ‘Markanduswami is my compass to you all; he shall show you all the spiritual directions,’ this being an indirect reference to Markanduswami’s career as a surveyor. Markanduswami attained mahasamadhi on May 29, 1984.”

One Day...

Yogaswami looked after everyone, and nothing was hidden from his inner vision. He knew exactly what was going on in his village, and all over Jaffna for that matter. Very little deserving his attention ever escaped it. A devotee recalls her time with Yogaswami during this period.

“Yogaswami went about like a king. I came to know of him when I married into a family who had taken him as their guru. The first time I saw him was the day after my wedding, on the 4th of September, 1951. I had not yet met Swami, though he lived very close to our house.

“We had returned from Malaysia after the Second World War. I first saw him on a visit with my husband and my father-in-law, Sir Vaithilingam Duraiswamy, who had known Swami since 1920. We took tea in a flask and fruits on a tray. It was about 7pm when we arrived at the small mud hut with roof thatched with coconut fronds. It was dark inside the hut as I followed my father-in-law and husband. There were no lights, only the camphor burning in front of Swami. When my turn came to fall and pray at his feet, I saw myself looking at a pair of eyes so powerful, as if they saw into you.

Close to the earth: Yogaswami envisioned a spiritual community of young celibate men who would grow food for pilgrims while following strict spiritual disciplines. The land was acquired during Swami’s lifetime, and the center manifested in 1965, just after his passing.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

One day at about 12 noon, when the sun was unbearably hot, an old woman came into the hut, panting and perspiring. She appeared to have come a long distance, and she was carrying a large jak fruit, since it was known this was among Swami’s favored foods. She unloaded the burden in front of the Swami and sat down with a sigh of happy relief. Swami watched all this and addressed the woman thus: “Look here, are you mad? Why did you walk all this distance in this hot sun carrying this huge jak?”

The woman waited for two minutes and retorted: “It is I who carried it all the way for you. It was my pleasure; why do you reprimand me for that? I am not asking for anything in return from you. I wanted to bring it to you, and I have brought it. Now let me rest for awhile and get back home. You keep quiet.” Thoroughly surprised at the woman’s innocent admonishing, Swami told her, “You can have a fine rest and also a life of peace and joy.” He had her served with a cup of coffee and told his devotees, “With one sentence she has shut my mouth. It was my fault to have blamed her.” He then gave her an orange and sent her home.

THE GURU’S SANDALS

Yogaswami had a pair of his guru’s wooden sandals enshrined behind a curtain in his single-room hermitage. To these, his most sacred possession, he offered worship each morning. His daily routine was to awaken early, bathe, pluck a few flowers and perform arati, passing burning camphor before them on a raised pedestal. These still remain today. It was his only personal worship, other than visiting certain temples. The sandals also reminded all who visited Yogaswami that, indeed, he too had a guru who had led him to the goal.

He was typically dressed in a white veshti that was forever and magically spotless, despite the dusty Jaffna roads. He often threw a white cloth of hand-woven cotton over his shoulders. His feet were clad in simple brown sandals, worn from his incessant walks but well kept. A few of his personal items remain today. A stainless steel water cup and shower towel with colored stripes are kept on his altar at Kauai’s Hindu Monastery, and the family of Ratna Ma Navaratnam, a close devotee, cares for his black umbrella.

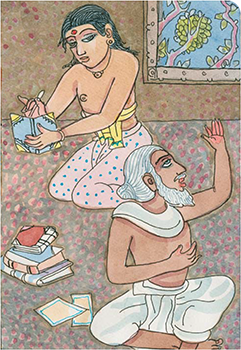

Swami performs daily worship to his guru’s sandals in his hut.

“We sat opposite him. He spoke to my father-in-law for a while, then turned his eyes on me and asked, ‘Can you cook?’ I replied, ‘Yes.’ He also gave me a Devaram book of Saint Tirujnanasambandar’s songs. After that, I came to cook for Swami nearly every day. We would often visit him in his hut. He drank his tea from a coconut shell. The shell kept the heat in, and most Jaffna people had them in their house.

“He also came for lunch the three years when my husband was stationed in Jaffna. My husband would read for him. He would say, “If Sorna reads, I can understand.” He had named my husband Sorna and wanted his brothers and sisters to call him by that name.

“The people of Jaffna treated him as their king. He walked about Jaffna, through the paddy fields and palmyra groves, visited houses and scolded people who had to be put right. In my father-in-law’s house his words were law. Most decisions to be made were put forth to Swami and his conclusion was carried out.

“Swami encouraged everyone to go to the temple. Once on the morning of the annual chariot festival at Nallur Temple, my father-in-law was still asleep, and we could not leave without his permission. It was 7am, and at eight the Lord would come out of the temple. Suddenly we heard Swami shouting in front of the house, ‘What are you all doing there? Get out and go to the temple! Arumugan comes once a year to bless everyone. Go!’ He was Lord Nalluran Himself, ruling his people. He called everyone by name.

“My mother was a great devotee of Lord Nalluran. As we lived close to Nallur Temple, she conducted her day according to the ringing of the temple bells. Getting up at 4am, she would say, “My Nalluran has gotten up.” Swami would often come and sit on one of the verandah chairs. He would look at her as if to say, “Don’t you know me? I am your Nalluran.’ He was a strength to the Jaffna people. He was their Nalluran.”

Occasionally Yogaswami refused to accept things, sometimes asking that food offerings be buried in the yard behind his hut. “Don’t even let the crows eat it,” he would shout. “It’s not fit for the crows to eat!” One day a man came with a tray of offerings. In the middle of the tray was a bag containing five hundred rupees, a goodly amount in those days. Those around watched him present the offering, speculating what Swami would do, for they all knew the money came from a venture Swami was not in favor of.

Usually in such cases Swami would not accept it. To add force to the refusal he might even send the tray and its contents sailing through the air with a strong throw. But this time, to everyone’s surprise, he instructed a devotee to distribute it to various people. Swami instructed, “Save a hundred rupees and take Vithanayar to the doctor. I’ve heard he’s ill. He won’t want to accept the money, so tell him he can pay me back later. Then he will accept.”

Entering the house, the devotee found Vithanayar sitting in the courtyard. Startled to see him appearing so fit, the man inquired about his health. Vithanayar said everything was fine, so the devotee gave him the money as Swami had instructed, which, true to life, was initially refused but finally accepted under the strict condition that it would be repaid.

Unsure of what to do next, the devotee decided to return to Swami when Vithanayar’s daughter motioned him aside and said that her father had a high fever and was quite sick, but was simply too stubborn to let on or do anything about it. Understanding this, he told Vithanayar that Swami had ordered him to take him to the doctor. He pleaded, “If you don’t go, I’ll be in trouble with Swami. And you know how that is.” The devotee continued to beg, “Please come with me, just to satisfy Swami.”

Vithanayar relented, and they set out to visit the doctor. Examining Vithanayar, the physician scolded the devotee for even moving him, much less bringing him in a car. “He has double pneumonia,” the doctor scolded. But when the man explained the circumstances, he understood. After administering some medication, he gave instructions to take Vithanayar home and put him to bed, adding that he would come by the next morning to check on him. The medicine, an expensive new antibiotic, cost almost exactly the amount Swami had allotted for the visit.

A Guru’s Chores

Swami arranged marriages, named babies, settled family arguments, helped devotees find homes to buy, got them jobs and generally mothered everyone. He kept all of Jaffna on its toes and made sure that people got what they needed and deserved. He gave and gave and gave and gave. He said, “We are in the tradition that gives. We give even to people who don’t deserve anything, to selfish and jealous ones.”

Inthumathy Amma recorded the testimony of Panchadeharam of Ariyalai, a schoolteacher who had gained much from his visits to Yogaswami through the years:

“Even though a year had passed since our marriage, my wife and I had no children. Due to financial difficulties, we were not disappointed. Even after two years, we were childless. During this time when we went for his darshan, Gurudeva asked, “You have no children yet, isn’t that so?” We replied, “Yes, Aasan.” Then he plucked a big grape from a bunch, gave it to my wife and said, “Do not give this to anyone. You alone must eat it.” My wife did accordingly. Next month we realized that she was pregnant.”

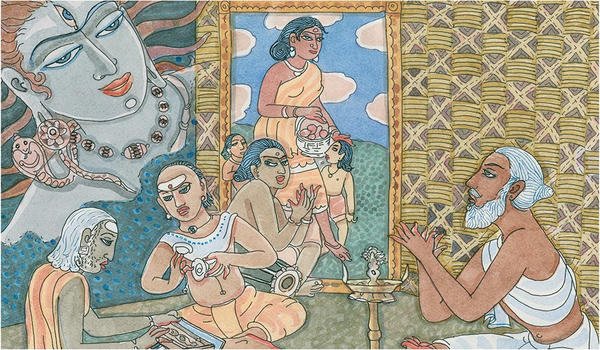

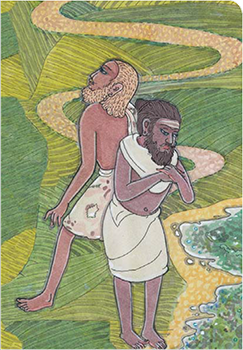

Magical moment: Chellappaswami kept camp in the chariot house at a Murugan temple. When Yogaswami passed by one day in 1905, Chellappaswami shook the bars and simultaneously shook his future disciple to the core.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

THERE IS ONLY ONE!

Chellappaswami’s insistence on the oneness of guru and disciple, in fact the oneness of everything, while strange to the average man, was a faithful expression of the ancient Agama texts, which decree: “‘Siva is different from me. Actually, I am different from Siva.’ The highly refined seeker should avoid such vicious notions of difference. He who is Siva is indeed Myself. Let him always contemplate this non-dual union between Siva and himself. With one-pointed meditation of such non-dual unity, one gets himself established within his own Self, always and everywhere. He who is declared in all the authentic scriptures as unborn, the creator and controller of the universe, the One who is not associated with a body evolved from maya, the One who is free from the qualities evolved from maya and who is the Self of all, is indeed Myself. There is no doubt about this nondual union” (Sarvajnanottara Agama 2.13-16).

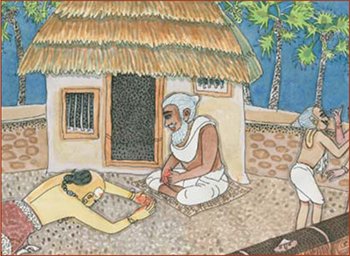

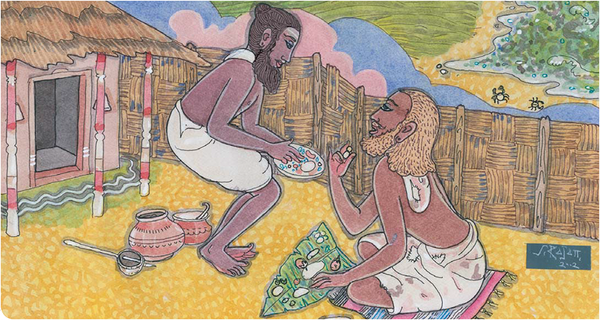

Yogaswami serves his guru lunch on a banana leaf.

“Who Do You Think You Are?”

OGANATHAN WAS WALKING ALONG THE ROAD OUTSIDE NALLUR TEMPLE. Sage Chellappaswami shook the bars from within the chariot shed, where he camped, and boldly challenged, “Hey! Who are you?” (Yaaradaa nee?). Yoganathan was transfixed by the simple, piercing inquiry. Their eyes met and Yoganathan froze. Chellappaswami’s glance went right to his soul. The sage’s eyes were like diamonds, fiery and sharp, and they held his with such intensity that Yoganathan felt his breathing stop, his stomach in a knot, his heart pounding in his ears. He stared back at Chellappaswami. Once he blinked, in the glaring sun, and a brilliant inner light burst behind his eyes. He later wrote of that moment:

OGANATHAN WAS WALKING ALONG THE ROAD OUTSIDE NALLUR TEMPLE. Sage Chellappaswami shook the bars from within the chariot shed, where he camped, and boldly challenged, “Hey! Who are you?” (Yaaradaa nee?). Yoganathan was transfixed by the simple, piercing inquiry. Their eyes met and Yoganathan froze. Chellappaswami’s glance went right to his soul. The sage’s eyes were like diamonds, fiery and sharp, and they held his with such intensity that Yoganathan felt his breathing stop, his stomach in a knot, his heart pounding in his ears. He stared back at Chellappaswami. Once he blinked, in the glaring sun, and a brilliant inner light burst behind his eyes. He later wrote of that moment:

He revealed to me Reality without end or beginning and enclosed me in the subtlety of the state of summa. All sorrow disappeared; all happiness disappeared! Light! Light! Light!

Waves of bliss swept his limbs from head to toe, riveting his attention within. He had never known such beauty or power. For what seemed ages it thundered and shook him while he stood motionless, lost to the world. He later described it as a trance.

To end my endless turning on the wheel of wretched birth, he took me beneath his rule, and I was drowned in bliss. Leaving charity and tapas, charya and kriya, by fourfold means he made me as himself.

The roaring of the nada-nadi shakti—the mystic, high-pitched inner sound of the Eternal—in his head drowned out all else. The temple bells faded in the circling distance as from every side an ocean of light rushed in, billowing and rolling down upon his head. He couldn’t hold on, not for an instant. He let go, and Divinity absorbed him. It was him, and he was not.

By the guru’s grace, I won the bliss in which I knew no other. I attained the silence where illusion is no more. I understood the Lord, who stands devoid of action. From the eightfold yoga I was freed.

Yoganathan stood transfixed, like a statue, for several minutes. As he regained normal consciousness and opened his eyes, Chellappaswami was waiting, glaring at him fiercely. “Give up desire!” he shouted. People were passing to and fro, unaware of what was taking place. “Do not even desire to have no desire!”

Yoganathan felt the grace of the guru pour over and through him, all from those piercing eyes. Such elation he had never known. Dazed, he saw that the guru intended to dispel all darkness and delusion with his words, which were beyond comprehension in that moment: “There is no intrinsic evil. There is not one wrong thing!”

Yogaswami later wrote of this dramatic meeting in a song called “I Saw My Guru At Nallur:”

I saw my guru at Nallur, where great tapasvins dwell. Many unutterable words he uttered, but I stood unaffected. “Hey! Who are you?” he challenged me. That very day itself his grace I came to win. I entered within the splendor of his grace. There I saw darkness all-surrounding. I could not comprehend the meaning. “There is not one wrong thing,’ he said. I heard him and stood bewildered, not fathoming the secret. As I stood in perplexity, he looked at me with kindness, and the maya that was tormenting me left me and disappeared. He pointed above my head and spoke in Skanda’s forecourt. I lost all consciousness of body and stood there in amazement. While I remained in wonderment, he courteously expounded the essence of Vedanta, that my fear might disappear. “It is as it is. Who knows? Grasp well the meaning of these words,” he said, and looked me keenly in the face—that peerless one, who such great tapas has achieved! In this world all my relations vanished. My brothers and my parents disappeared. And by the grace of my guru, who has no one to compare with him, I remained with no one to compare with me.

As Yoganathan tried to comprehend the experience, his guru had already forgotten him there. Chellappaswami was scanning distant rooftops, mumbling to himself and nodding in accord with all he was saying, then began walking away. Yoganathan started to follow when the sage called back over his shoulder, “Wait here ’till I return!”

It was three full days before his guru came back, and the determined Yoganathan was still standing right where he left him. Chellappaswami didn’t speak or even stop. He motioned for Yoganathan to follow, leading him to the open fire pit where the sadhu prepared his own meals. There he served Yoganathan tea and a curried vegetable stew, then sent him away.

He didn’t welcome or praise his new disciple; he didn’t say to come back or not to come back. He didn’t have to. Yoganathan knew he had been accepted. And his training began—the first chance he got, he bent to touch Chellappaswami’s feet, and his guru bellowed in dismay. Drawing back, the sage scolded him, “Don’t even think of it!” Yoganathan was bewildered, but he obeyed, and his guru calmed down. “You and I are one,” he said. “If you see me as separate from you, you will get into trouble.”

Devotees would write down Yogaswami’s spoken gems of wisdom. These were later compiled in a small book called Words of Our Master.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Come, offer worship, O my mind, to Gurunathan’s holy feet, who said, “There is not one wrong thing,” and comforted my heart. Come swiftly, swiftly, O my mind, that I may adore the Lord who on me certainty bestowed by saying “All is truth.” Let us with confidence, O my mind, hasten to visit him who at Nallur upon that day “We do not know” declared. Come soon and quickly, O my mind, Chellappan to see, who ever and anon repeats, “It is as it is.” Come, O my mind, to sing of him who near the chariot proclaimed, “Who knows?” with glad and joyful heart for all the world to know. Come now to Nallur, O my mind, the satguru to praise, the king of lions on tapas’s path whom nobody can gauge. Come with gladness, O my mind, our father to behold, who of lust and anger is devoid, and in tattered rags is clothed. Please come and follow me, O mind, to see the beauteous one, who mantras and tantras does not know, nor honor or disgrace. Come, O my mind, to give your love to the guru, free from fear, who like a madman roamed about, desiring only alms. Come, O my mind, to join with him who grants unchanging grace and is the Lord who far above the thirty-six tattvas stands.

So simple is the path, yet you make it hard by holding onto the idea that you are you, and I am I. We are one. We look at the sun and feel its rays. The same sun, the same rays, the same nerves doing the feeling. That also happens when we look within. We feel the darshan of the Lord of the Universe, Siva without attributes. The same darshan is felt by you and me alike. Not your Siva or my Siva; Siva is all. We must burn desire and let the ego melt in the knowing that Siva is all; all is Siva. There are millions of devas to help you. You need only implore them and keep yourself steady through sadhana. Then you will come to see all as one and will taste the divine nectar.

• • • • •

There is a chair at the top reserved for you. You must go and sit in that chair. From there you will see everything as one. You will know no second. That is a state unknown even by the saints and celestials. Buddha attained that state and came down to help others. Christ knew that state and also tried to bring others to it. Many others no one has heard of have known that state. That chair is there, reserved for you. It is your job to occupy it. If you don’t do it in this lifetime, you might do it in the next or in the next or in the next. It is the only work you have to do. There are those who can fly to the top like birds. It is not a simple thing to control the mind. It cannot be done in a day, or even in a year. Through constant effort thoughts can be controlled a little. In this way the uncontrollable mind can finally be brought under control. This is the supreme victory.

• • • • •

Call not any man a sinner! That One Supreme is everywhere you look. Ever cry and pray to Him to come. Be like a child and offer up your worship. Forswear all wrath and jealousy; Lust and accursed alcohol eschew. Associate with those who practice tapas, And join great souls who have realized Self by self.

• • • • •

Everyone must find out the path that suits him. The train can only run on rails.

• • • • •

As we kiss our children every day before going to work, so must we daily love the Lord.

• • • • •

If you remove illusion, you will see that Siva pervades everything.

• • • • •

If you want liberation in this birth, make your mind a cremation-ground and burn all your desires to ashes.

• • • • •

The world is an ashram, a training ground for the achievement of freedom. Each one does his part according to his own measure.

• • • • •

You must meditate in the morning and evening and at night before you go to bed. Just pronounce the name ‘Siva,’ and sit quietly for about two minutes. You will find everything in your life falling into place and your prayers answered.

• • • • •

Let happiness and sorrow come and go like the clouds.

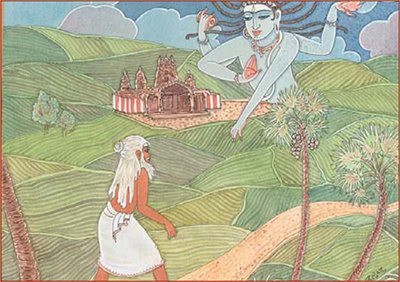

Sacred words: Swami’s songs of philosophy and ecstatic states of mind were often composed at the feet of Thayalnayaki (Goddess Parvati) at a shrine in a nearby temple where he could inwardly hear Her ankle bells ring.

The Teachings of Yogaswami

E SPOKE TAMIL AND ENGLISH FLUENTLY BUT KEPT A SINGLE BOOK IN HIS HUT, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. It was all he needed, that and his guru’s guidance. Often Yogaswami would sing spontaneously, and if fortune smiled a devotee would write it down to preserve for others to enjoy. Sometimes he would arrive at a devotee’s house with a song written down that had come to him from within, gifting it to the family. Swami’s compositions consist of 385 Natchintanai songs, twenty letters and about 1,500 terse sayings.

E SPOKE TAMIL AND ENGLISH FLUENTLY BUT KEPT A SINGLE BOOK IN HIS HUT, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. It was all he needed, that and his guru’s guidance. Often Yogaswami would sing spontaneously, and if fortune smiled a devotee would write it down to preserve for others to enjoy. Sometimes he would arrive at a devotee’s house with a song written down that had come to him from within, gifting it to the family. Swami’s compositions consist of 385 Natchintanai songs, twenty letters and about 1,500 terse sayings.

Swami’s teachings explore the mysteries of yoga, disclose the divine experiences on the path and praise Chellappaswami and the Mahadevas, especially the supreme Lord, Siva—avoiding the intricate complexities of the Tamil language. He spoke forcefully, artfully, but in everyday terms. Indeed, his language was incisively simple, and even his profound Natchintanai were couched in common vocabulary, unlike the classical verses of Tirumurai and earlier saints. Natchintanai is a personal diary of sorts, recording Swami’s experiences, his realizations, his anguish and his hopes. The language and style are straightforward. His poems on Murugan and Siva have such a feel of familiarity that you could reach across the page and touch them. He talks to the lizard and the peacock with the confidence that they, too, can help his quest. He uses folk songs and dances, indicating that he was communing with the common man. He goads us on to the feet of the guru on the path, reminding us often that is what a human birth is for: to serve Siva, to meditate on Siva, to find union in Siva.

Photo Gallery

Devotees gather in Yogaswami’s hut after his hip surgery. Swami was secretly photographed walking the Jaffna lanes, his umbrella fending off the tropical sun. The chariot house in which the tall chariot is stored and where Chellappaswami often camped (with Nallur Temple behind). Inset: A woman worships at the bilva tree under which Chellappaswami sat. Markanduswami, who was so loved by Yogaswami that the guru built this hut where the lifelong brahmachari lived out his hermit’s life.

Yogaswami’s hut in Columbuthurai. Inside the austere dwelling. The shrine holding Swami’s guru’s holy sandals which he worshiped daily. Yogaswami’s body is prepared for cremation. Devotees carry their guru’s bier to the cremation grounds in 1964.

Lord Siva beats His drum fourteen times, issuing forth fourteen primal sounds to create the universe. High in the Himalayas, siddha Nandinatha sits with his eight yogic disciples to teach, for the first time in known human history, the revelatory truths of the monistic tradition of Saiva Siddhanta. His disciples are Sivayoga Muni, Patanjali, Vyaghrapada, Tirumular and the four sages, Sanaka, Sanantana, Sanatana and Sanatkumar. These are the forerunners of the Nandinatha Sampradaya, to which Yogaswami’s Kailasa Parampara belongs.

A short video about the parampara and additional images and links to the stories and to The Guru Chronicles, the book from which this story is excerpted, can be found here: