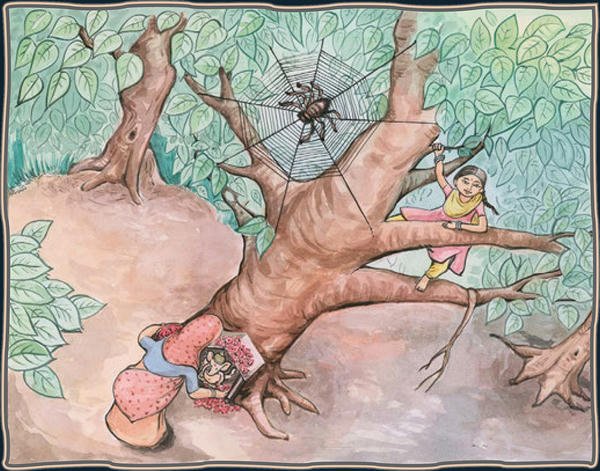

Reaching the second limb, the girl watches a devotee far below, offering flowers and loving devotion to Lord Ganesha, enshrined at the foot of the banyan. The youth wonders if the spider in its web also knows of the ten observances and if he has a yoga of his own to practice.§

The niyamas are 1) hrī, “remorse,” being modest and showing shame for misdeeds; 2) santosha, “contentment,” seeking joy and serenity in life; 3) dāna, “giving,” tithing and giving generously without thought of reward; 4) āstikya, “faith,” believing firmly in God, Gods, guru and the path to enlightenment; 5) Īśvarapūjana, “worship of the Lord,” the cultivation of devotion through daily worship and meditation; 6) siddhānta śravaṇa, “scriptural listening,” studying the teachings and listening to the wise of one’s lineage; 7) mati, “cognition,” developing a spiritual will and intellect with the guru’s guidance; 8) vrata, “sacred vows,” fulfilling religious vows, rules and observances faithfully; 9) japa, “recitation,” chanting mantras daily; 10) tapas, “austerity,” performing sādhana, penance, tapas and sacrifice.§

In comparing the yamas to the niyamas, we find the restraint of noninjury, ahiṁsā, makes it possible to practice hrī, remorse. Truthfulness brings on the state of santosha, contentment. And the third yama, asteya, nonstealing, must be perfected before the third niyama, giving without any thought of reward, is even possible. Sexual purity brings faith in God, Gods and guru. Kshamā, patience, is the foundation for Īśvarapūjana, worship, as is dhṛiti, steadfastness, the foundation for siddhānta śravana. The yama of dayā, compassion, definitely brings mati, cognition. Ārjava, honesty—renouncing deception and all wrongdoing—is the foundation for vrata, taking sacred vows and faithfully fulfilling them. Mitāhāra, moderate appetite, is where yoga begins, and vegetarianism is essential before the practice of japa, recitation of holy mantras, can reap its true benefit in one’s life. Śaucha, purity in body, mind and speech, is the foundation and the protection for all austerities.§

The yamas and niyamas and their function in our life can be likened to a chariot pulled by ten horses. The passenger inside the chariot is your soul. The chariot itself represents your physical, astral and mental bodies. The driver of the chariot is your external ego, your personal will. The wheels are your divine energies. The niyamas, or spiritual practices, represent the spirited horses, named Hrī, Santosha, Dāna, Āstikya, Īśvarapūjana, Siddhānta Śravaṇa, Mati, Vrata, Japa, and Tapas. The yamas, or restraints, are the reins, called Ahiṁsā, Satya, Asteya, Brahmacharya, Kshamā, Dhṛiti, Dayā, Ārjava, Mitāhāra and Śaucha. By holding tight to the reins, the charioteer, your will, guides the strong horses so they can run forward swiftly and gallantly as a dynamic unit. So, as we restrain the lower, instinctive qualities through upholding the yamas, the soul moves forward to its destination in the state of santosha. Santosha, peace, is the eternal satisfaction of the soul. At the deepest level, the soul is always in the state of santosha. Therefore, hold tight the reins.§